I am not a linear thinker. I did not even know that a person could think linearly until a professor pointed out to me that I do not. I am more of a pinball thinker. If you’re familiar with pinball machines, you’ll have an idea of what I mean.

For those who aren’t familiar, a pinball machine is a game table with a clear, sealed cover. To play, you pull back a spring that shoots a small ball into the play area, where the ball bounces off various obstacles. The player can affect the ball’s movement by remotely moving levers. Lights come on. Buzzers sound. Points are scored. The ball’s movement can be unpredictable and erratic.

That’s how I think.

My thoughts are unpredictable and erratic. Ideas ping off each other. Inspiration lights up more ideas. Sometimes I can’t come up with anything good, and it feels like I just keep dropping the ball without scoring any points. And just as a player gets better when they practice, the more I think (and write) about something, the clearer my thoughts become.

My pinball brain has trouble staying contained in a word processing document. I may be writing a story, but I’m also having ideas about why there aren’t octopuses in this story world and how late my character likes to go to bed. Where do I put that? Do I ignore it, even though my character’s bedtime is the key to solving the mystery? Do I type it right into the story, even though it has nothing to do with the current scene? Do I create a new file for the scene it goes in? Do I create a new file to collect all my ideas?

These are the issues I struggle with. It’s organization, and it seems like the answers should be simple. But it hasn’t been simple for me.

Inline Annotations

There is a tool in Scrivener called inline annotations that helps me with this problem. It’s recently become a favorite, probably because of the stage of editing I’m in. I’m past major developmental edits where I completely rewrite big chunks of the book. I’m still moving things around, rewriting, asking a lot of questions, etc., but on a smaller scale. For my current scale of work, inline annotations are proving to be a trusted friend.

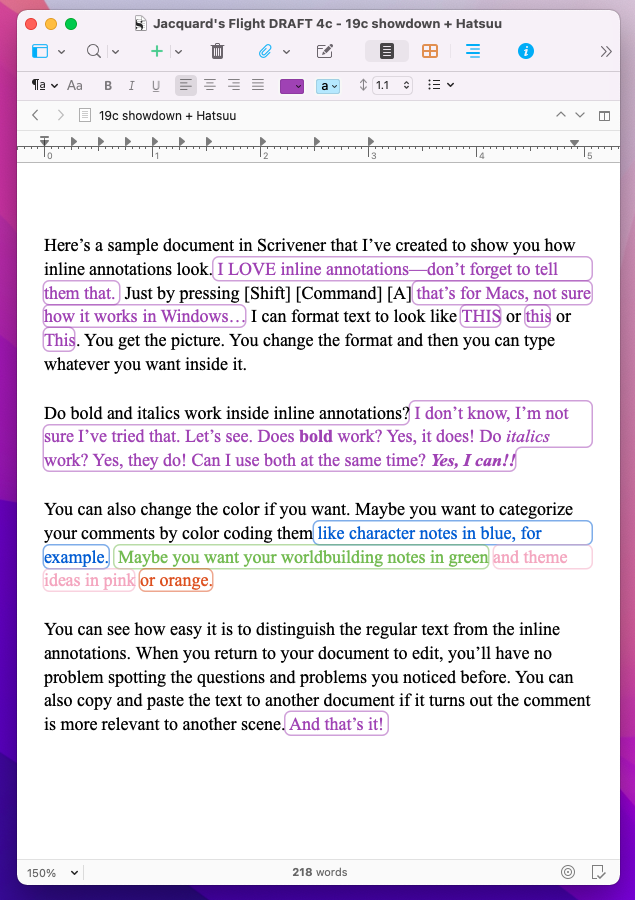

At their most basic, inline annotations are simply a different format, like italic or bold. Specifically, the format changes the font color (you can choose the color) and puts a bubble around any continuous block of text formatted this way. Very hard to miss.

Just like for italic ([Command] [I])1 or bold ([Command] [B]) there’s a simple shortcut to format these annotations: [Shift] [Command] [A]. The formatting works in the same way. You can toggle it on and off by selecting text and pressing the shortcut keys. Or you can turn on the formatting with the shortcut keys, type your annotation, and then press the shortcut keys again to turn off the formatting.

Because inline annotations are not used in published work (plus they’re unique to Scrivener), I never use them as part of the text. So when I see an inline annotation, I know it’s a note to myself.

This allows me to spill my pinging thoughts. If I’m writing dialogue, and I realize I need to figure out why one of the characters keeps sneezing, I can press [Shift] [Command] [A] and type my idea right where I am, without disrupting the flow of my writing. I know I’ve got a reminder for later.

Why Not Comments?

There are other ways to make notes to yourself in Scrivener. Comments, for example, link to text and are listed in a sidebar. The linked text is reformatted with a different color and underlined. Like inline annotations, they stand out from normal text and can be created with a shortcut. Comments can certainly be used the way I use inline annotations, but there are two reasons I prefer the latter. First, I like the simplicity of seeing my thoughts inline with the text that inspired them. Second, I don’t like having the sidebar open—it clutters my desktop and forces me to keep checking outside my document.

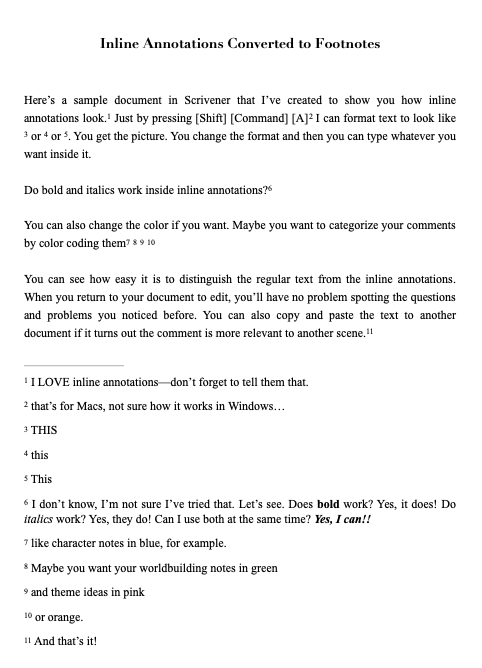

While editing, there are stages where I print out my manuscript and edit on paper. You would think the inline comments would make it hard to read the text cleanly, and they would if they retained the same format, but Scrivener has other options. I’ll tell you my favorite: footnotes.

When I compile my manuscript for printing (this is a weird Scrivener thing—tell me if you want more about this in a future post), I have Scrivener convert my inline annotations to footnotes. Scrivener moves all inline annotations to the bottom of the page, and numbers them sequentially. It’s beautiful. When I read the manuscript, I can easily read straight through the text. If I want to see what past me was thinking, I glance down at the handy dandy footnotes. Brilliant!

1These keystrokes are for Mac Computers.

What a neat tool! I’m always looking for ways to get distracting thoughts off my mind (usually onto a list) to focus on work at hand. Sounds like you have a great strategy for that in Scrivener. Would love to hear more about how you use it!

It is pretty cool! Maybe I’ll do a more in-depth post on how I use this tool…